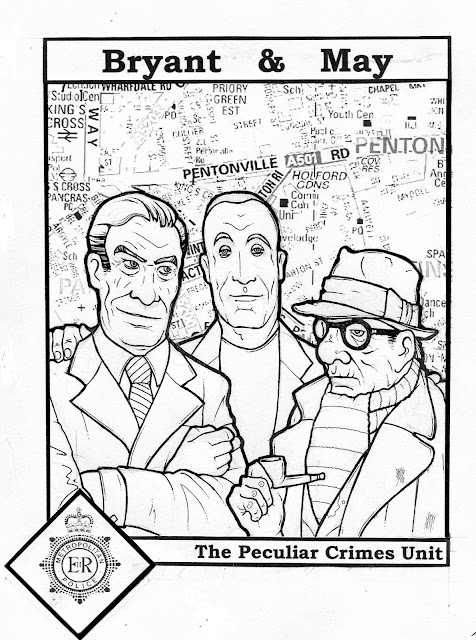

Keith Page draws 'em so much better...

Christopher Fowler is a

fine crime writer, and so he ought to be as one of the judges for the yearly

Golden Dagger Award. It’s been more than twenty years since I first came upon

his books where with a little money in my pocket I bought Roofworld and spent a

fine summer day reading it. At the time in the Elephant and living the

counter-culture lifestyle it was a book that appealed to many of us, what with

me and mine being rather the dregs of the city but surviving rather well – and

living as I did at the time on the fifth floor. So too for the love of London,

a hobby horse of my own going back to my Lambeth roots and my granda Bill

showing me the city inside and out.

I was

pleased to find a couple of years later another book by the same author, this

one Rune. Then onwards to Calabash towards Bryant & May, the elderly

detectives of the Peculiar Crimes Unit who had appeared in the background on a

number of occasions and now are about to see the tenth novel in their own series where

the crimes step in and out of a London both contemporary and folkloric.

A year

ago I spoke to Chris on the phone whilst passing through London, to be told

‘I’m in a meeting with Patrick Stewart, but I can’t really talk about it.’

Shortly thereafter and in one of his many decent London pubs he said, ‘So this

project with Patrick Stewart,’ followed by, ‘Now where did I put my wallet?’

I went to

the bar…

More

recently and Chris kindly agreed to answer a few questions for the Slide. This

is rather apt as in many ways the Slide is here because of Chris. I was one of the winners of his Campaign For Real Fear and his fellow judge Maura McHugh

seemed rather surprised I had no web presence when gathering up our details.

Meanwhile Chris had a blog. And if he could produce regularly I thought, why

not I?

So then.

You were born in Greenwich

and it’s fair to say that you are very much the London-boy. Much of your work

is centered upon London, the city you know so well – but what is the romance of

it, what is London to you?

It hasn’t been preserved,

with old and new towns, so it has mythologized parts of itself, with just

enough left to show hints of what once was. My father remembered Paternoster

Row, the street of bookshops behind St Paul’s that was bombed flat in the Blitz,

and my aunts recalled waiting for the drawbridges around the Isle Of Dogs to

rise (actually I remember those too) but they’re gone now, and I find myself

going back to try and reboot this amorphous city of memories.

Would London be a sibling,

a parent or a lover?

A stern, patrician,

unforgiving parent.

Comparing your memoir Paper

Boy with Psychoville the parallels are clear. Whilst of course you draw on what

you know, how much was Psychoville an exorcism of that period in your life? And

dare I ask, given the similarities how did your family take the story?

Actually, ‘Psychoville’ is

a melding of my story and my younger brother’s. In a way it was a dry run for

‘Paperboy’,but I loved the idea of visiting unstoppable revenge on the soulless

commuter towns that sprang up in the 70s/80s. I’m not sure what my family

thought; they were a bit blasé about my writing career by this time; ‘Oh, he

makes things up. It’s not a proper job.’ Etc.

Another work that concerns

childhood is Calabash, or if not childhood, then youth certainly. At sixteen

Kay is another with an unhappy life but here he escapes into an exotic land of

the mythical east. I confess Calabash is my favourite of your novels, but it

does stand aside from the rest of your stories. The escape is gentler here than

in Psychoville, warmer perhaps, and whilst it is hardly children’s-fiction

would it be fair to say it shares or draws something from that genre? Calabash

is what I would recommend to those grown but who enjoyed Philip Pullman, to

clarify.

It’s my favourite too, and

I’m gutted that it flopped; it was wrongly sold at existing fans of my work and

is the odd volume out (apart from my children’s novel ‘The Curse of Snakes’). I

tend to return to the Calabash theme; the moment when you must put away your

imagination and take on the responsibilities of adulthood, a break-point that

appears in coming-of-age novels. I was thinking specifically of ‘Billy

Liar’,the UK equivalent of ‘Catcher In The Rye’ and one of my favourite books.

What I like best about the book is its central paradox; the more time hero Kay

spends lost in his imagination, which heals him, the more he loses his ability

to survive as an adult. I’d love to get it republished and read by teens, as

it’s a timeless subject.

What then did you read as a

boy, that which would be considered children’s literature?

I’m not sure I ever did

read specifically children’s literature, although certainly books like ‘The

Swiss Family Robinson’ and ‘Twenty Thousand Leagues Under The Sea’ were

standard works for British kids. Jules Verne featured heavily for boys born in

the 1950s.

In Paperboy much is rightly

made of the library. Whereas I grew up buried in books the library was still my

first and easiest place-away-from-home. Up here certainly it’s a social place,

a meeting hall almost and especially for parents. A chum of mine would have it

though that libraries are little more than dinosaur zoos set up as a sop for

Edwardian philanthropy.

Libraries are under threat

in many places, yet with the growth of the virtual ability for people to own

every book, ever, and then some, what place do you believe libraries hold in

these more modern times?

A huge place, if they are

reinvented properly. A few weeks ago I gigged at two libraries, one in Deptford

(a deprived, predominantly black neighborhood) the other in Islington (wealthy

middle class and bookish).

The Islington gig was a

disaster – hardly anyone there, an old-school library in a rundown Victorian

edifice that virtually defies you to enter it. Deptford’s new library is a

blinging golden box in the middle of its main shopping street, and was full of

kids reading and using its multi-media facilities – this is the much derided

‘Idea Store’ rebrand and clearly works.

You finished school on the

Friday, started work on the Monday. Eschewing university or polytechnic you

went straight into (I believe) marketing or advertising? As an avowed film freak

(and indeed the title of the second as-yet unreleased part of your memoir) was

this a particular role, or a route to your later working as part of the British

film industry?

No, it was my route to

being a writer. I had Oxford-level grades but I wanted to start learning the

craft of writing, not its classical history, which I felt I could go back to

later. So it proved; a great many of my heroes had trained in advertising and

journalism, and it gave me an invaluable five years of understanding precision.

I left when I’d learned

enough, and set up a company.

Since there still was a

British film industry at the time what was it then that led to its subsequent

demise?

It had already fallen to

its knees, the victim of targeted destruction from the US, where vertical

integration meant they were able to buy up all exhibition outlets and own the

entire production chain. Margaret Thatcher’s disastrous dumping of the tax

break for shooting in British studios was the final nail in the coffin.

What was there at that

time, what genius or madness that no longer flourishes?

We had a profoundly

eccentric view of the world that started in the 1950s with the Ealing comedies

(watch ‘Passport to Pimlico’) and blossomed spectacularly in the 1960s with

everything from ‘Oh What A Lovely War!’ to ‘The Devils’.

As a part of The Creative

Partnership which film do you recall most fondly as having worked on?

I have happy memories of

working with John Cleese on ‘A Fish Called Wanda’, and being on set almost

every day of the Bond film ‘Goldeneye’.

And naturally enough, which

with the most shaking of hands about the tumbler late at night?

The latter, drinking late

with the stunt team in Monte Carlo.

When I first saw shots of

free-running and parkour the first novel of yours I read, Roofworld, jumped to

mind. I’ve seen shots of scripts developed from the novel sufficient in

combined weight to brain a small rhino yet it’s lived in development hell long

enough to have paid off the mortgage there and now rent out rooms to younger scripts.

How close did we actually come to seeing (what is arguably) your most cinematic

work on the big screen?

Very close indeed. We had a

director, start date and cast from Paramount. To this day I have no idea why it

was pulled from schedules. I’ve been astoundingly unlucky on that front.

I say ‘arguably’ since this

year’s Hell Train is openly the film that Hammer or Amicus never made. As a

writer you’re a grafter. It’s a job and you don’t seem to spend much time in a

big shirt decrying the elusive muse. Hell Train is a fun book – and I mean that

as a compliment – so how much of it was a chance for you too to change gear? To

just plain enjoy writing something almost for your own enjoyment?

All my books are honestly

written for me to enjoy, with the exception of ‘Snakes’, which I hated every

second of. Hell Train actually had a tortuous not-at-all-fun birth as a

screenplay. I’m glad it doesn’t show!

Spanky, your novel with the

cover (and you know which one) set to make nice straight guys more interesting

to interesting women – concerns a Faustian pact made by the protagonist Martyn

with the eponymous demon. Now, is Spanky Martyn?

Of course! Almost filmed

– again – by Guillermo del Toro, it was pipped to the post by ‘Fight Club’, a

much better film than a book.

Let’s turn to Bryant &

May.

August sees the release of

the latest book in the series featuring elderly detectives John May and Arthur

Bryant utterly failing to find bodies by riverbanks or to waffle on about their

alcoholism or broken marriages. There are no running gun battles but rather

mysteries ranging from both traditional locked-room to more modern urban fears-

balanced by the two protagonists themselves being between them something of

both the old and the new. Bryant & May have been in the background to your

novels for some time now (Rune, Soho Black, and Disturbia) before with the

Water Room realising their own series. The Invisible Code now the tenth you’ve

said that you’re now working on a more conventional airport brick. My question

is, won’t that piss off Arthur?

Not really, because the

airport brick inevitably has turned out to be deeply quirkly, hinging on an

outrageous slight-of-hand. But there’s no humour in it, something I consciously

planned for this.

Fans often like to read

more of the same. You’re fortunate that you’ve been able to skip about the

genres a fair bit and the fans of John and Arthur are likely to be happy enough

to sit with a pint whilst the blockbuster takes wings knowing they’ll be back

soon enough, but do you envision a time when John or Arthur pass away? There’ve

been a couple of scares, and they’re getting on a bit now (bless)?

I answered this in a panel

yesterday. It’s fiction; they can live forever. Although I love playing with

the idea of age, which comes up again in the new book.

The Leicester Square

Vampire was first mentioned (to my knowledge) in Roofworld. There a former case

for the more conventional DCI Hargreaves, but later one of B&M’s before

they rose to act as the pin for the Fowler milieu. I admit I was a little

surprised by what came of that in Ten Second Staircase, always thinking it

would be their last case, or the one ever unsolved. Was this a time when Ten

Second Staircase might well have been the last B&M novel?

Short answer; no. I just

wanted to put the bloody case out of the way, and it was useful as a

back-story.

What I like about the

novels is that the relationship between John and Arthur is not laboured.

Touches like their habit of walking the river and John’s estranged family are

present but there’s no lengthy inner voice worrying about feelings and drinking

problems, no needy characters being more important than the story (despite the

story in many ways being them). Nonetheless, and between you and I, is Arthur

gay?

No, he follows the classic

Golden Age line of having once been in love (I think I pushed her off a bridge)

and now dedicated to nothing but work.

A number of people have

asked about earlier cases for John and Arthur. I’m not sure how reluctant you

are with this since their age and perspective is fundamental to the theme of

the cases. Full Dark House was as much to do with the beginnings of what later

books portray so much as the pair, but do you worry that stories concerning the

1960s and 70s will be a bit like finding out your grandparents were raving

hedonists and not just nice old people that came up with the Airfix of a

birthday? That a reader might not quite look at them the same way again?

Good point – I don’t think

they’d fit very comfortably in the B&M timeline because they would have to

do very sixties things. There are a few short stories featuring them in

different time periods (I may do a collection eventually) and the graphic novel

features a 1968 story.

The Casebook for Bryant

& May is out in October, a graphic novel from what little I’ve seen

lovingly illustrated by Keith Page. You’re a comic fan, and there was Menz

Insana back in the 90s, what was it about this format that you found to be

particularly useful for a B&M case that you could not perhaps have realised

as pure prose?

That’s precisely it –

comics require a totally different approach, and ‘Casebook’ allowed me to

produce a pitch-perfect parody, if you like, of the kind of very British comics

I had as a child. The tone is completely different, much whackier.

And speaking of comics, and

that photo of them all around you – Lois Lane and Jimmy Olsen?

Come on – there’s a whole

chapter dedicated to Lois Lane in ‘Paperboy’!

Peter O’Donnell is said to

have joked that he was in love with Modesty (Blaise) and friends with Willie

(Garvin). They live and work fairly close to you, so how would you describe

your relationship with each when you meet up for a fictional pint?

Bryant and May are me and

Jim Sturgeon, my business partner, whom I miss dreadfully (he died of lung

cancer). For a while it became a way of staying in touch with him, but the

stories grew away as I let him go. Still, I’m May and my ramshackle, rude side

would be Bryant.

Lastly, living as you do in

a glass lair atop and overlooking King’s Cross where even the carpets are

transparent and your cat invisible – where the hell do you put the bodies?

I used to think they were

at my house in France, where all my other stuff went, but I sold that. I’ve

bought a very dark, cluttered place in Barcelona now, so I’ll ship the corpses

there.

My

thanks to Chris Fowler for the interview. Bryant & May and the Invisible

Code is out on August 2nd. The Casebook of Bryant & May in

mid-October.